History of the Thermes of SPA

Balneotherapy as we know and practice it today goes back to the dawn of time and of our civilisation, in particular Roman. Bathing is the oldest therapy in the world. And in terms of our own history, we don’t dismiss the possibility that Spa’s name is derived directly from the Latin word sparsa, spargere: to gush out.

HISTORY OF THE THERMES OF SPA…

Known for its thermal springs, Spa really began to thrive in the 16th century when the reputation of the waters led to significant trade.

Known for its thermal springs, Spa really began to thrive in the 16th century when the reputation of the waters led to significant trade.

At this time, it was above all curing by ingesting large quantities of water that prevailed.

By way of anecdote, the spa client, known as a « Bobelin », had an ivory dial which he used to keep count of the quantity of water consumed. He also furnished himself with aniseed or cardamon to assist in digesting this very mineralised water and to help take his mind off its taste.

Spa was the first to export its water as early as the 16th century to nearby regions and then across the whole of Europe, thereby taking with it the growing reputation of its cures.

The term Spa became a generic term for thermal baths in English and in several other languages.

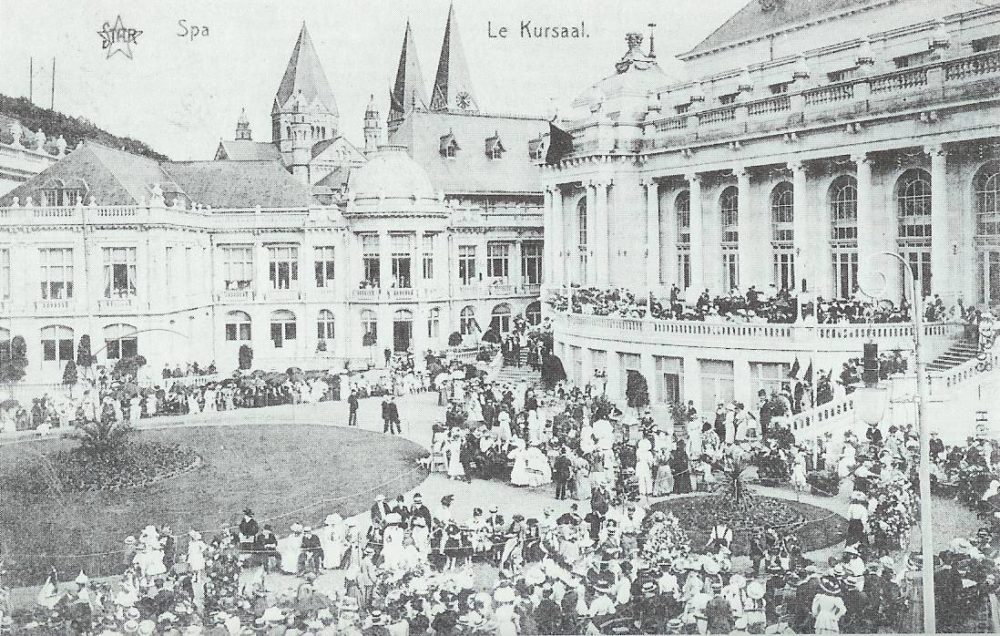

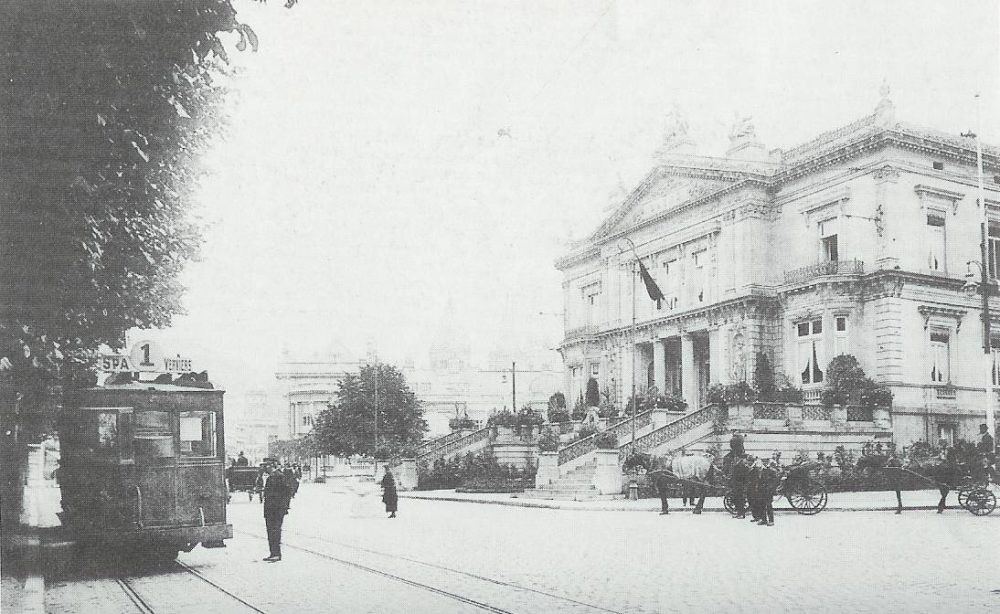

Spa having become a popular meeting place for the nobility and European Bourgeoisie, the emperor Joseph II (after his visit in 1781) dubbed the city the “Café de l’Europe“.

And it was also in Spa that the first modern casino was born, the Redoute, at the initiative of co-mayors Gérard Water and Lambert Xhrouet. Visitors to Spa include Victor Hugo, Czar Peter the Great, Alexandre Dumas père and Meyerbeer.

Marie-Henriette associated her name and destiny with the city. In fact, she lived in Spa for several years and contributed to its fame.

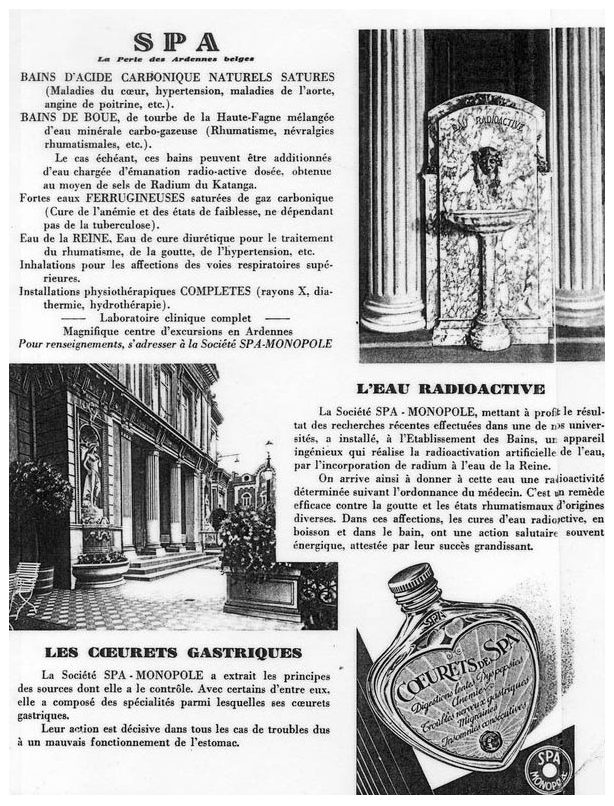

A little later, the entire royal family of Belgium visited Spa, including the Queen Marie-Henriette who died there in 1902. She associated her name and destiny with the city. In fact, she lived in Spa for several years and contributed to its fame. A spring essential to the life of Spa and the life of the Thermes is named after her: The Marie-Henriette spring.

Giacomo Casanova, a connoisseur of the great Spas of Europe, wrote in The Story of my life that “Spa, […] this place where, in the name of I know not what convention, all the nations of Europe flock once a year in the summer to engage in a thousand follies; I have made them mine like everyone else”, adding that “in this hole called Spa”, under the pretext of “taking the waters”, we rushed there “for business, for intrigue, to play, to make love, and also to spy”.

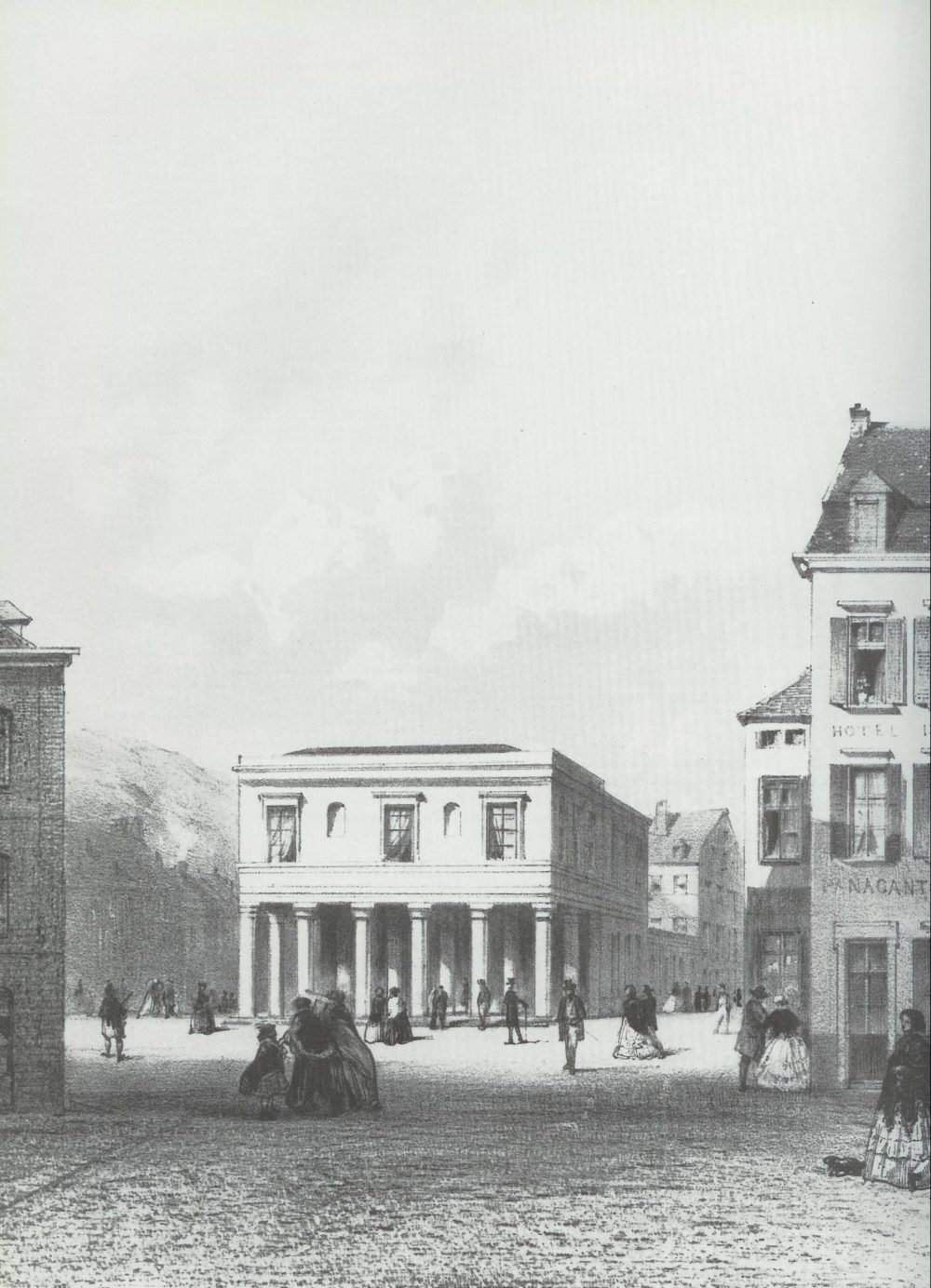

Most of the great names of the 18th century rubbed shoulders there, kings and queens and illustrious figures, whether they belonged to the nobility, the clergy or to the affluent bourgeoisie. As soon as they had arrived, they were inscribed on the “List of Lords and Ladies”, which each year included 600 to 1200 curists, accompanied by their retinue. At the time, these numbers represented a considerable influx.

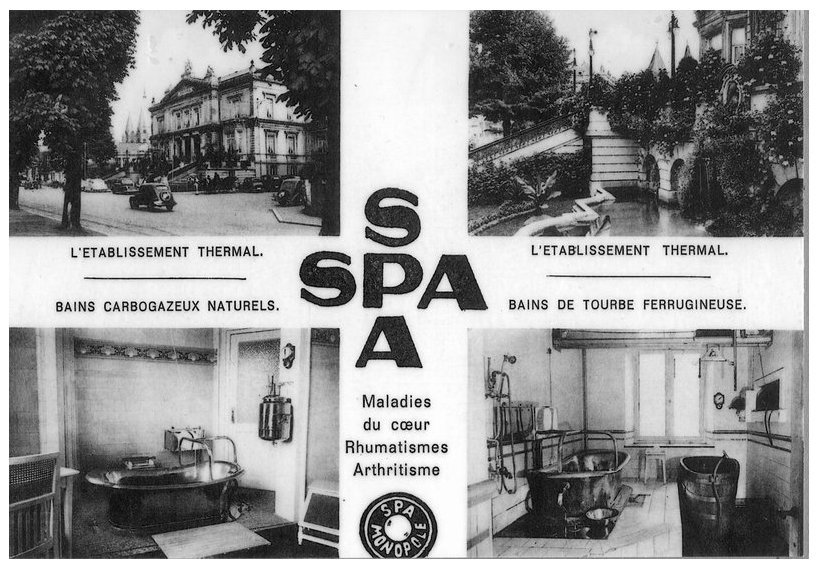

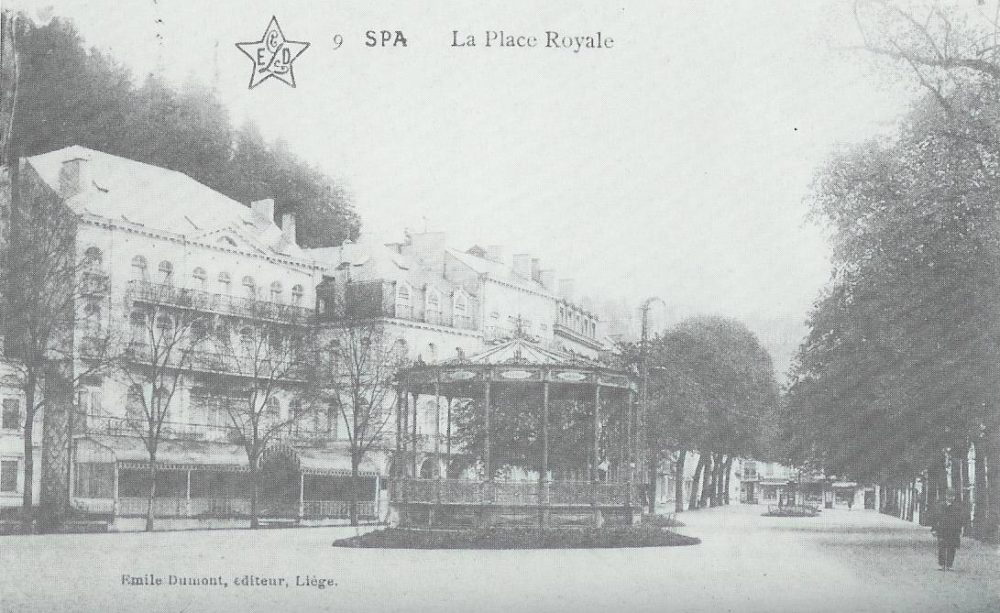

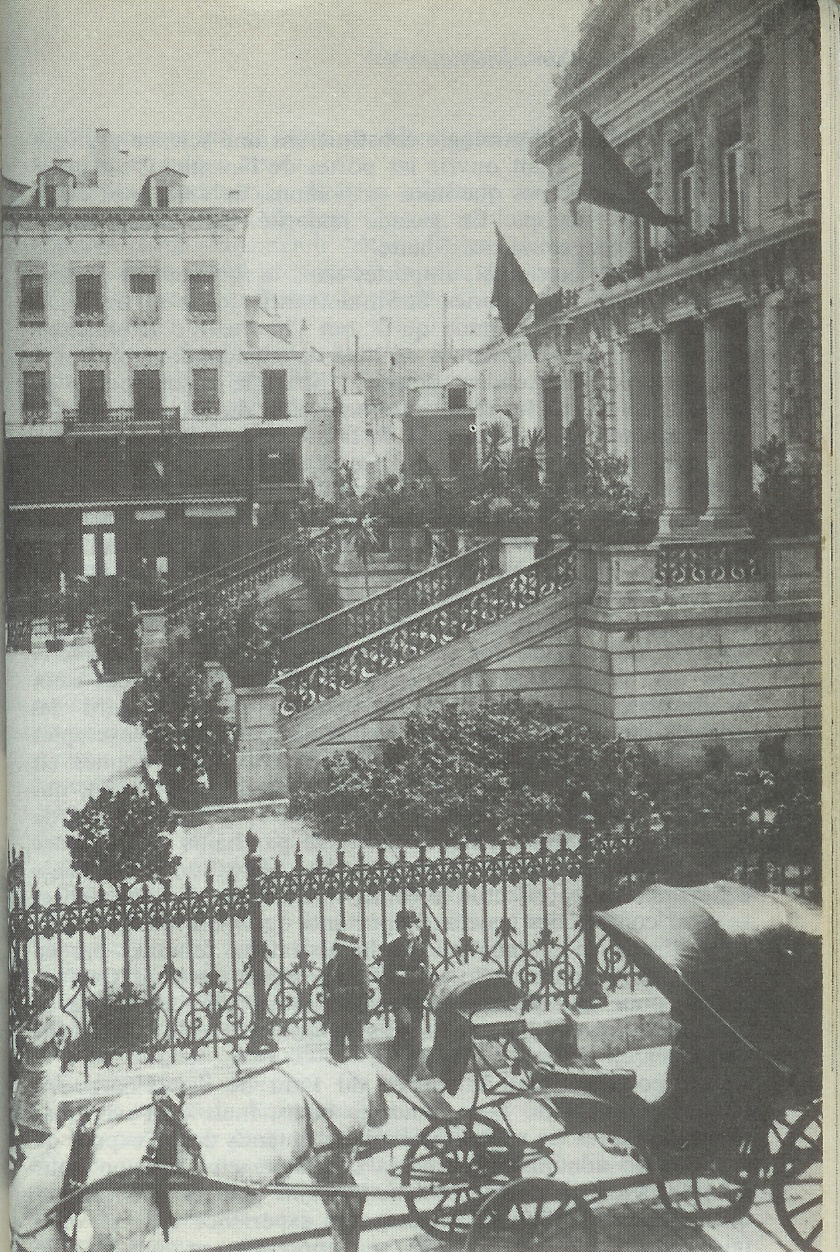

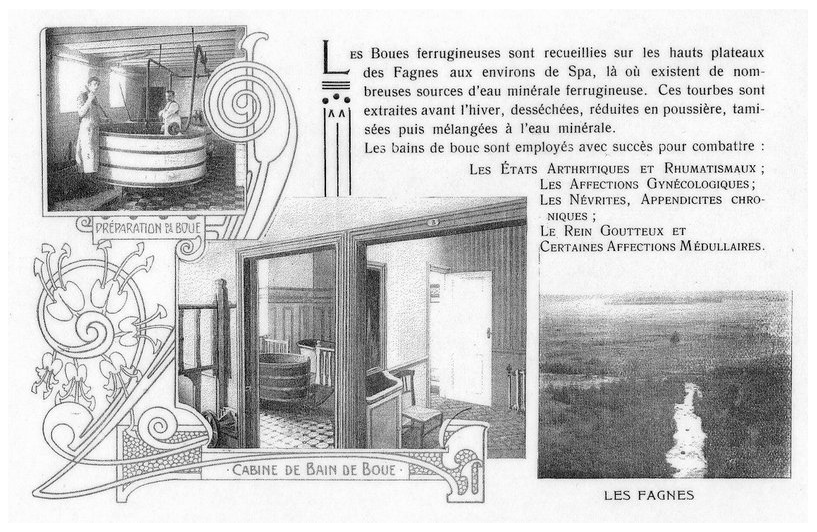

Spa did not escape from the upheavals and rigours of the revolutionary period. Curist visits to the ville d’eau became less frequent. At the height of misfortune, in August 1807, a fire destroyed the heart of the city. Spa did not recover its international renown of the 18th century. At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, the city experienced significant urban redevelopment with the construction of the Leopold II gallery and the Pavilions in 1878, the Pouhon Pierre-le-Grand in 1880, the Villa Marie-Henriette in 1885, the Lac de Warfaaz in 1892, the Eglise St. Remacle consecrated in 1886 and, of course, the Thermes building in 1862, which is still visible today. This thermal infrastructure would include 54 equipped baths and peat baths, opening in 1868.

The City modernised the thermal building in 1905 but the First World War took away any tourist activity, transforming Spa in a vast lazaretto for the German army.

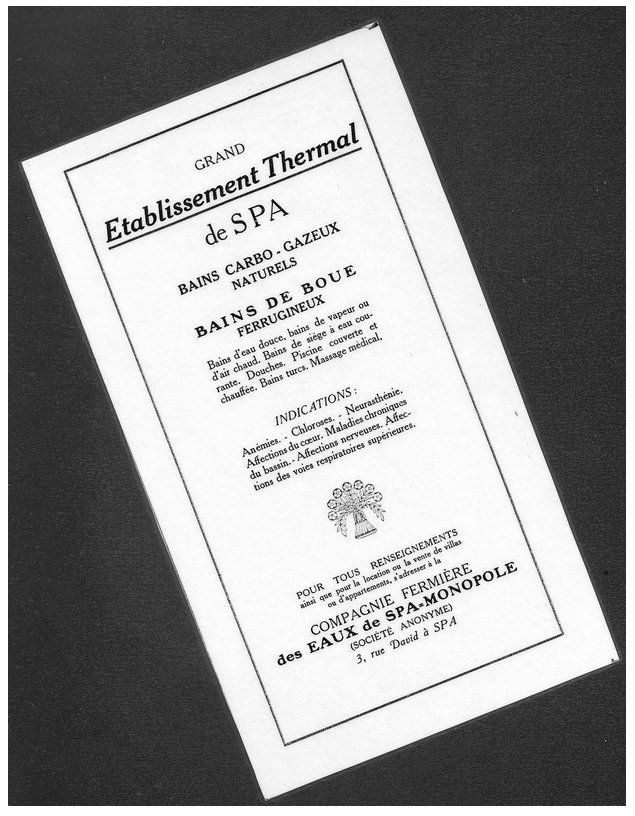

One of the most important events of the period between the two world wars was certainly the creation of the company Spa Monopole by the Chevalier de Thier in April 1921. The trade in water that had flourished until the 18th century, after a lengthy dry spell until the 19th century, would then take on a highly industrial dimension.

The post-war years saw the arrival of social bathing with the inauguration of the Heures Claires in 1949 The announcement of the end social security reimbursements for thermal-bath cures at the end of the 1980s prompted the city of Spa and the company Spa Monopole, concession holder of the spa house, to begin to think about renewing the concept of balneotherapy. This time of reflection resulted shortly after in the finalising of the project to build a new thermal centre on the Annette et Lubin hill.

The new building that houses “Les Thermes de Spa” owes its design to the architect Claude Strebelle, also the architect of the Place Saint Lambert in Liege.

Since 1868, water is the sacred element of the Thermes of Spa; everywhere present in a preserved nature, it is charged by the force of the earth.

The growth in the number of curists is directly linked to decisions taken regarding social matters. As such, there were more than 12,000 curists when social security was partially reimbursed, this dropping to fewer than 5,000 curists in 1987.

The following years saw visits increase little by little, but it was clear that the thermal baths needed to be adapted to this new situation. The new spa house was opened in 2004 and visitor numbers are rather encouraging: 54,112 visitors in 2004, 96,607 visitors in 2005, 175,000 visitors in 2015.

Would you like to know more about the succession of Spa’s thermal bath houses throughout the centuries? [Cliquez ICI]